Yesterday I was invited to give a public talk about one of the books that inspired me from the distant past. I had to decline the offer because of the timing but it got me thinking about what that book might be.

Rummaging around my old children’s books I managed to find the one.

Usborne’s The Spy’s Guidebook.

I loved this book as a kid. I must have read it hundreds of times – and for some reason I have two copies. One quite battered and loved to death, and the other in much better condition. Opening it after all these years brought back a flood of memories.

The Spy’s Guidebook was, I think, three single titles in a series compiled into one thick volume.

(As an aside, there was another ‘detective’-oriented series – one volume of which, Catching Crooks, I managed to leave with my teddy in a bag by the side of the road on a trip to Canberra one school holidays. I was distraught and I remember, when we got home, my mum and dad vainly calling the police to see if it had been handed in. Being the 70s, it had and a few days later there was a amusing puff piece in the Daily Telegraph about the police finding my bag with Catching Crooks in it. I really should find and scan that clipping)

But back to the Spy’s Guidebook. As a kid this book was like stepping into a world where the walk between your house and your best friends’ houses was filled with danger and, of course, many opportunities to try out the stealthy tricks from the book. We’d make secret code wheels, write messages in invisible ink, try to move without being noticed. The quirky illustrations and raincoated spies, straight out of Spy vs Spy, help make the book so approachable and engaging.

I don’t buy the idea that this sort of ‘childhood secret club‘ behaviour has disappeared with the omnipresence of portable games and digital intrusions or squeezed out by the revoting concept of ‘tweens’. Some of this ‘secret club’ behaviour has just migrated to the web and to these communication devices themselves – I wish I’d had a iPod Touch or DS as a kid – we could have done some awesome codebreaking and crazy adventuring with them! And I’m always amazed by the imaginative worlds even the most cotton-wooled kid manages to conjure up out of the most meagre of raw materials. You see this happening with kids at the park everyday – if you look.

It seems that the Spy’s Guidebook is still in print although apparently it was revised in the 1990s when it came with a CDROM (!!). But I’m pleased I have a late 19070s copy to pass on to my kids and I hope they get as much from it as I did. If you see a copy in a secondhand store, grab it. It really is an excellent read.

Last time I wrote I was heading off to Japan for the school holidays. We survived that trip with the help of this handy and fun little guide. We even managed to spot some of the monsters contained within along the way!

Yokai Attack! is the kind of book that as a 9 or 10 year old I would have pored over for months.

Short, written in a ‘vital statistics’ style, and for those who just want to dip in and out from time to time, it details roughly 40 strange Japanese monsters, or more accurately, ‘spirits’. Some of these are from traditional folklore like Onibaba, the mad old woman who ate her daughter and grandchild, and the Kappa, the cucumber-obsessed flatulent amphibian that drags unsuspecting people under in Japan’s waterways (and after whom cucumber sushi rolls – kappa-make are named!). While others are better known from Manga and Japanese horror films.

If you’ve watched Miyazaki’s wonderful animations Spirited Away, My Neighbour Totoro or Pom Poko, then you will know a fair number of these creatures already – which is why this book is equally fun reading for young and old. Spirited Away features, amongst other spirits, a Nopperabo (“no face”) who visits the bathhouse and Pom Poko is all about the antics of the Tanuki, the magical Japanese racoon dogs with unfeasibly large testicles (!) who play shapeshifting tricks on humans and like to party and drink themselves into a stupor. My children had great fun pointing out the Tanuki statues we saw outside of noodle bars in Kyoto, Osaka and Tokyo!

The book is illustrated by Tatsuya Morino with amusing cartoons of each monster. Here’s the bath dwelling Akaname. This one uses its tongue to attack and clean all those who bathe in dirty bathrooms . . . .

For younger children these monster stories need adult supervision. Quite a number are creepy in a Japanese horror movie kind of way. But if you are planning a visit to Japan with children then I’d highly recommend it as it provides many new ways to view the many odd things your children will encounter and ask about (even if your only questions relate to the omnipresent Tanuki statues).

Similarly if your children are fans of Miyazaki’s films the book offers an additional layer of interpretation, pitched just right for their attention span and curiosity.

In preparation for another visit to Japan I’ve been reading the children some Japanese folk tales – as well as watching large swathes of the Studio Ghibli films, paying particular attention to the shape-changing Tokyo-dwelling racoons in the quirky Pom Poko. I probably would have introduced the awesomely weird Great Yokai War had they been a bit older.

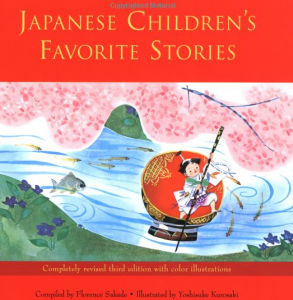

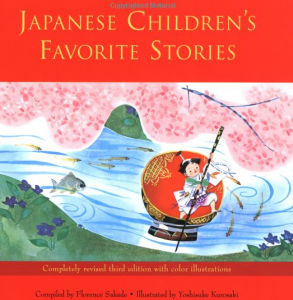

I was looking for some good, well illustrated, collections of stories and came across Florence Sakade & Yoshisuke Kurosaki’s Japanese Children’s Favourite Stories at a local bookshop. Originally compiled in 1953 from stories in an English-language version of a Japanese children’s magazine of the time, I bought the third edition (2007) which has lovely coloured illustrations and an audio CD of the stories for the car.

I’ve been really impressed with the attention that these stories have managed to keep when I read them to the kids. The stories are the right length to get through a few in a night. We’re particular fans of the Why The Jellyfish Has No Bones and The Old Man Who Man Who Made Trees Blossom – both stories with absolutely horrible evil protagonists; and of course, The Rabbit In The Moon is a great short story which helps explain why the ‘rabbit is making moon cakes’ at full moon.

Recommended.

(And, coming back to the Great Yokai War, I’m really hoping we can pick up a copy of the Shugeru Mizaki’s Yokai Encyclopedia – but in the meantime The Obakemono Project is a fantastic online resource for the weirdest Japanese goblins!)

I’ve never read the Ramayana nor really delved deep into Indian mythos. Brought up on the Greco-Roman and Chinese pantheons, the only other mythos I really explored intently as a child were Egyptian (no child can really resist pyramids?) and Norse (Thor! Loki!).

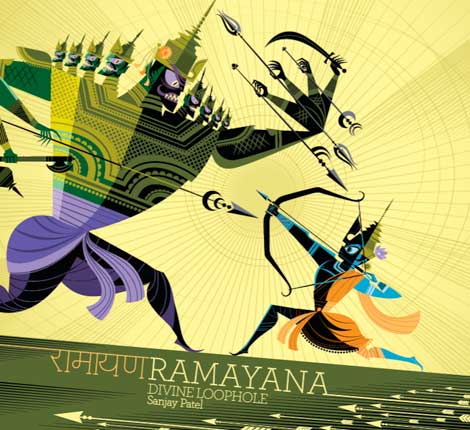

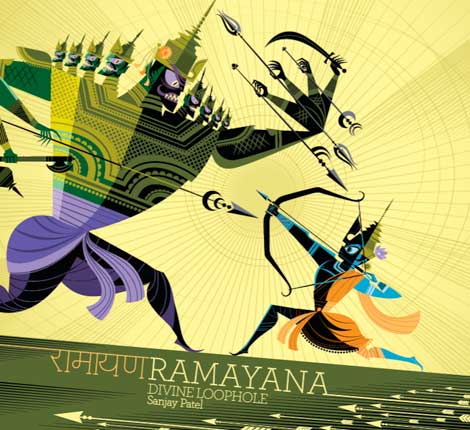

However tonight I read my youngest the first half of Sanjay Patel’s seriously abridged Ramayana (24,000 verses condensed to 107 pages!).

Patel is probably best known to those in the illustration and design world as one of the Pixar animation team. And here in Ramayana: Divine Loophole he tells the general story through vibrant illustration and some not-quite-so-vibrant text.

I really can’t fault the digital illustrations. They are stunning and stylised to capture immediate attention – indeed, they reminded me most of the style of The Incredibles – one of the Pixar titles on which Patel worked. The demons are menacing and fierce without being terrifying, and the colour palette is completely saturated, vibrant. The heroes bright and bold. (Check out Patel’s site Ghee Happy for some spreads from the book.)

The text, for the most part, is functional. But there are some clunkers. I’m not a fan of unnecessary colloquialisms like this – “But [Soorpanaka] was love struck, so much so that she transformed herself into a beautiful maiden and tried making a pass at the blue prince by showing off some of her dance moves”. They end up cheapening the story. Fortunately there aren’t too many instances of these.

Slightly problematic, at times, too is the contrast on the text. With almost edge to edge illustrations there are a quite a few pages where the small point text vanishes. The worst offenders being the pages with pale yellow text on an orange background (ugh!). I almost unintentionally skipped those paragraphs!

The final third of the volume, after the main story, is a collection of key characters, gods and demons; a map of the story locations; and several pages of process sketches.

When should children start on graphic novels & comics? Well there’s a question.

I can’t remember when I started reading comics.

It was some time in the early years of primary school. And I can only really remember that because I got in trouble for running a comic lending business which lasted all of a few weeks. Somehow I found a stash of cheap Richie Rich and Caspar comics in this newsagent a little past my school in Balmain and I bought up a pile of them.

For some reason they had some kind of magnetic pull. Given the narratives were so terrible, perhaps it was the weird black & white advertisements for sea monkeys or that the lame stories that were completely foreign to my experience of the world to that point (largely a result of only being allowed to watch the ABC TV, the public broadcaster, and no commercial channels).

They were also very cheap.

And I figured being cheap I could, with the help of one of the more maligned characters of the class acting as ‘enforcer’, bring a bag of comics to school and ‘rent’ them out for a few cents a day.

I can’t quite remember how this little bit of capitalist entrepreneurialism came to an end, only that it did. One day I had my two foot-high of comics confiscated from my desk and then it was over. I seem to remember, too, that one of my friends – totally out of character – ‘borrowed’ one of the comics for an ‘extended period’.

Around the same time I devoured the entire Tintin series in a fortnight – as fast as I could get them all out of the library with borrowing limits – and it wasn’t until the subcultural legitimation of ‘graphic novels’ in the late 80s, early 90s that I got back into an occasional read. And of course, when I was in Brussels in the late 90s I made sure I visited the Musée Hergé.

So, given my experience of comics wasn’t grounded in any kind of parental encouragement – in fact the opposite (it was ‘proper books’ only) – when is the right time to start introducing Tintin and other comics into the reading pool?

I’m not quite sure when it is ‘appropriate’ to introduce ghost stories to children but I reckon if there are tooth fairies who exchange money for enamel and calcium, and trolls that might leave treats under the bed, then there must also be less savoury magical creatures too.

In the late 60s and early 70s Ruth Manning-Sanders published a great series of fairy tales from around the world in volumes organised by the creatures present. This one, A Book of Ghosts & Goblins, is one of the best in the series with some quite scary short stories for children.

I was reading the short Spanish story The Ring to my 6 year old and it brought back vivid memories of hearing it the first time as a child myself. A man finds a ring on an unearthed skeleton in a disturbed graveyard and gives it as a present to his wife. Then that night the ring’s owner comes back to claim it . . .

There’s some great Estonian stories of nasty goblins as well as some enjoyable African and Siberian contributions too.

Try to find a copy in your local public library.

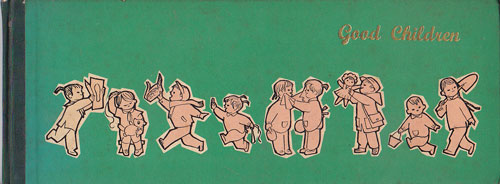

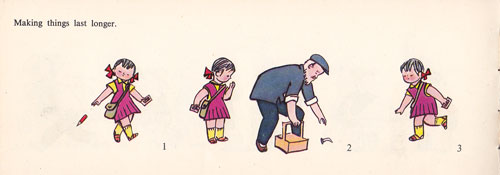

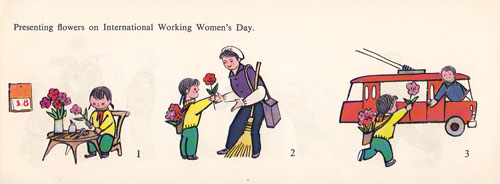

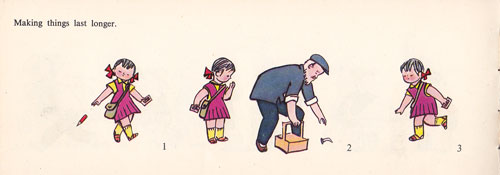

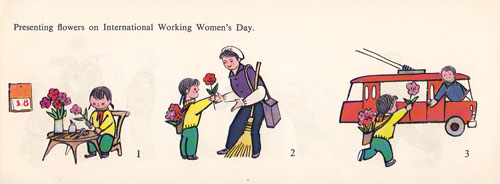

I’m not quite sure why I ended up with this as a child. But here it is, a 1974 propaganda book from the People’s Republic of China’s Foreign Language Press.

Essentially a pictorial guide with English text to being a ‘good child’ it offers helpful guidance on how to behave on International Working Women’s Day, and how to make the most of what you have, repairing broken toys, putting friendship first, helping old people. These are good upstanding things to do and the quaint pictures are, well, quaint. In fact, if it wasn’t for the ‘shoes for a people’s soldier’ page, this is entirely what you’d expect from a Sunday School book of the period.

In an age where children seem to get whatever they want it is a good idea to show them that it doesn’t have to be like that, and for the vast majority of the world, it isn’t like that at all.

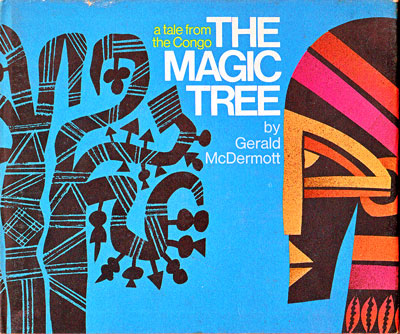

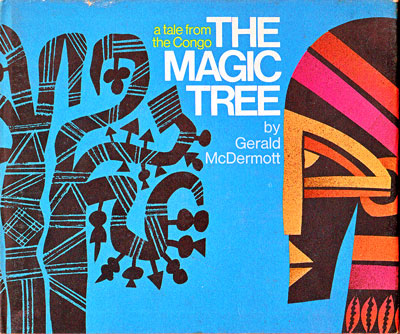

Gerald McDermott’s The Magic Tree is a not a tale with a happy ending – indeed the final pages are deliciously ambiguous.

First told as an animated short film in 1970 and then published in book form in 1973, The Magic Tree is apparently adapted from a traditional Congolese folktale. It tells the story of two brothers, one favoured by their mother, Luemba, and the other ‘ugly’ and cast aside, Mavungu. Mavunga leaves his family home and travels down the river to where he finds a tree and frees a beautiful princess from its magic spell.

Mavungu is transformed and a village springs up around he and the princess. Eventually Mavungu’s family hears of his fortune and travels to visit him. Mavungu feels the pull of the family home but is reminded by the princess that he has promised never to speak of the magic tree and its spell. His family leaves but Mavungu decides later to pay his despicable mother another visit and he cannot hold his tongue – all is revealed. Mavungu flees only to find that everything is gone.

The story’s end – told entirely without words – is jarring in a way that opens up the narrative for discussion. What happens now to Mavungu? Why was his mother so wicked? Why is this so unfair? Although these are unpleasant questions, you can almost see them playing out in the little listeners minds.

Beautifully illustrated with an almost wood-cut feel and with great use of dark blues and orange tones, the story’s atmosphere carries well. Also, I think that this book must of have been my first mass exposure to Helvetica as a child. The contrast between the jerky lines of the illustrations and the straight functionalism of the type is lovely too.

I’d be keen to see the short animation the story was evolved from. McDermott has some of his other animations from the period freely available via the Academic Film Archive and the Internet Archive.

A Halloween story illustrated by J.Otto Seibold was almost certain to be a winner. Seibold is probably best known for the slightly demented digital illustrations and his Mr Lunch series. You might also know his work from Olive.

I picked this one up at the Giant Robot store in San Francisco after a surprisingly short stop at Amoeba Records.

In Vunce Upon A Time a vegetarian vampire called Dagmar finds his secret supplies of lollies have run out. Despairing, one of his friends, a skeleton, tells him of a human tradition called Halloween where lollies are in plentiful supply. Although the prose is rather clunky, and the story convoluted – far too little is made of Dagmar’s vegetarianism – Seibold’s garish and colourful illustrations carry the attention and interest of the young ones. There’s a fantastic double page spread where Dagmar soars high above the town on Halloween night – revealing a town swarming with a cornucopia of costumed beasts which makes for a good bit of ‘spotto’. And, in fact, the assorted lollies on the inside flap always end up being “shared” between us, the readers.

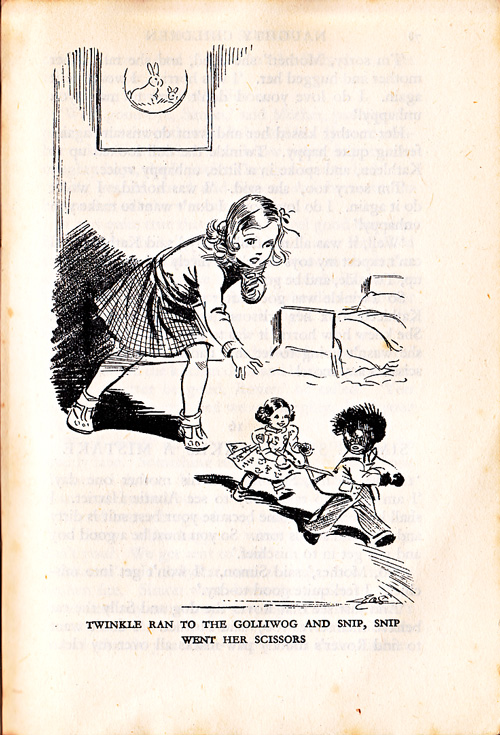

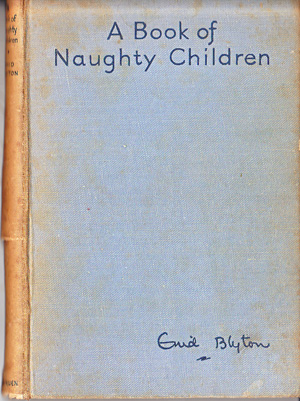

This book used to be my mum’s. She got it at “Christmas 1946 from Auntie Nellie”. Published during World War 2, I’m pleased to report that inside it has a little insignia stating – “This book is produced in complete conformity with the authorized economy standards”. It has stood up pretty well considering that, just a couple of frays on the spine, and a bit of dusty mould.

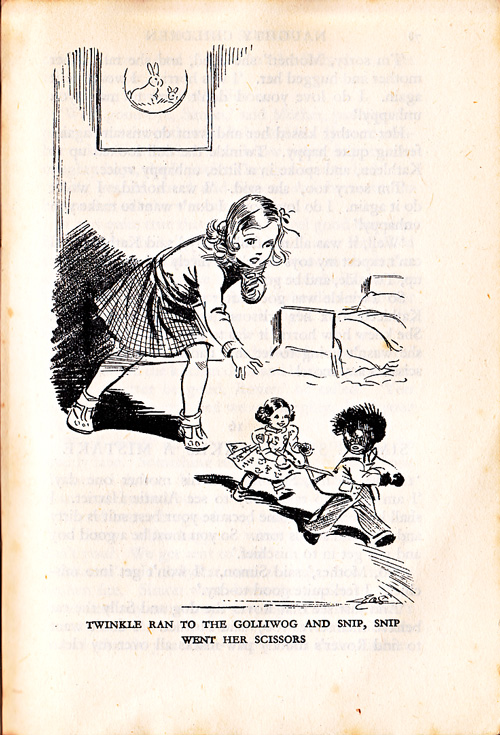

I remember studiously reading several Blyton series as a child – Wishing Chair, Magic Faraway Tree, and, of course the 21 odd volumes of the Famous Five (In fact I vividly remember watching the late 70s TV series after school and was excited to find much of it on YouTube recently). No doubt my mum read me this when I was small, too. For all the criticism of Blyton’s stories – and there’s been a lot of it over the years – this collection of very short stories is great reading in these modern times.

It is full of all the things ‘we’ don’t do now – whacking the kids when they misbehave, letting them run wild on the streets and the like. Whilst parenting styles have changed for many in the West nowadays, I quite enjoying reminding my children that things weren’t always like that. The look of horror on their little faces is always priceless.

There are of course, gollywogs, which need a little more contextual explanation.