Being a hoarder I managed to keep several boxes of children’s books from my own childhood. They’ve moved house with me and I’ve been paring them down slowly.

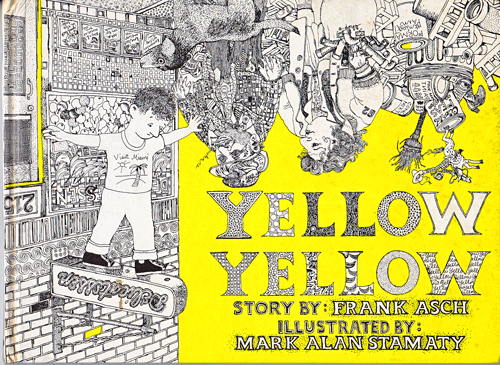

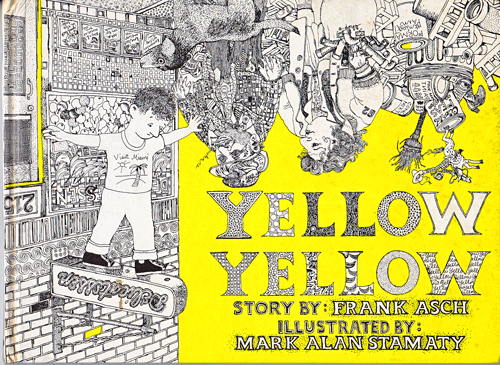

One of the first to be retrieved from the boxes upon the arrival of child #1 was Yellow Yellow. Dating from 1971 (although the edition I have is from 1973) and one of the earler books from Frank Asch, Yellow Yellow is the story of a boy who finds a yellow workman’s hat which changes his life. The real action for small children, of course, takes place in the illustrations from Mark Alan Stamaty – one of his first contributions to children’s books it seems.

Each page is full of intricate details, quirks, MC Escher-isms and visual jokes that make repeat readings particularly enjoyable. The illustrations also have a suitably psychedelic quality to them which always elicits puzzled questions like “why does that chicken have a two bodies but only one face?” and “that man has his head on backwards doesn’t he?”.

There’s a great moment midway through where the boy finds the owner of his yellow hat – one of those rare moments where the physicality of the book as an object becomes apparent and important.

Neither Asch’s or Stamaty’s websites really mention the book at all – although it does seem to be outlandishly priced second-hand on Amazon.

But if you see it in a used bookstore snap it up. I’ll definitely be passing my copy on to the next generation.

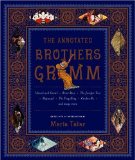

Several months ago one of my friends was asking on Twitter about good ‘classic’ children’s books and I recommended this one as possibly the best collection of Grimm’s fairytales. I had just bought a copy and we’d started going through it as bedtime reading.

Apart from being entirely un-Disney-fied, what is especially nice about the Tatar edited collection is that each story comes with copious sidebar annotations for the reader. These sidenotes are very useful at explaining the underlying meanings in some of the choices of words and character traits in both the very well known and lesser known stories.

Snow White, Cinderella, Rapunzel – they are all here amongst the 37 stories for children – but the original versions with the witch who has to dance to her death in burning hot iron shoes, doves that peck the eyes out of the evil sisters – and all those sorts of violent and explicit moral guidances that have been removed from the modern popularised versions. Indeed, reading these the clear role that fairytales and myths played in educating children about the dangers of the forest, of strangers, and of life, comes across loud and clear – indeed, quite graphically.

The king’s mother was an evil woman . . . . A year later, when the queen gave birth to her first child, the old woman took it away and smeared blood on the queen’s mouth while she was sleeping. Then she went straight to the king and accused the mother of eating the baby. [from The Six Swans]

The contemporary sanitising of fairytales effectively eliminates the critical role of stories in allowing children to explore their own boundaries with their imaginations. Instead the sanitisation of Disney, or worse the Barbie range of Fairytopia hideousness, simply renders any sense of moral message or warning mute for the sake of shifting more branded merchandise.

Illustrated lightly with drawings and paintings from different versions of the stories, this has been a great volume to have on hand to counter the inevitable influx of pink princess dross with a bit of grit.

On Friday night I was wandering up through Newtown before a friend’s art event and stopped in at our local bookshop – you know, one where the staff actually know about the books they sell, and write little ‘reviews’ on the ‘staff picks’.

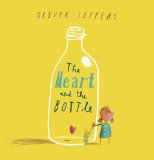

And there it was in the children’s section – the new Oliver Jeffers’ book, The Heart and the Bottle. Given the enthusiasm we’ve had for Lost & Found (which I’ll write about later), I picked it up without much hesitation.

In short, the narrative revolves around a girl who is fascinated with the world around her before she finds (her Dad’s) chair empty one day. She puts her heart in a bottle, grows up and loses her interest in the world around her until she encounters a child who shows her how to get her heart back. On first reading to G she immediately asked ‘what happened to her Daddy?’ – quickly picking up on the subtext of the story.

We’ve been back to it several times this weekend already. (K reckons we should buy a copy for a couple of our adult friends.)

Not surprisingly for a Jeffers’ book, the illustrations are full of tiny details – especially the girl’s fascination with the creatures of the sea and how they work – and I’d recommend removing the dustjacket as underneath lies a fabulous visual collage. G and I have been going through the illustrations trying to figure out their secrets.

In fact, dustjackets – yes or no? That’s another post I should get around to writing.

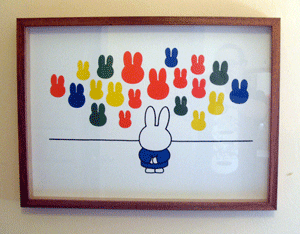

If there is one baby book that sums up an aspirational middle class life then it is probably Miffy at the Gallery. Apparently it has always been a big seller at the Art Gallery of NSW bookshop, as well-to-do parents think what an excellent role model Miffy will play for their child.

In fact, I came across Miffy at the Gallery via a poster shop in Tokyo in 2003. I was walking through one of the few enormous malls in Odaiba – a beach and amusement park on reclaimed land in Tokyo bay – and chanced upon a design store. Flicking through the posters – reproductions of design classics including a lovely series of 1950s Olivetti advertising – there was a simple Miffy poster featuring the image from cover of the book with no surrounding text.

Thinking of a future when there might be children around, I bought the poster and when the children came a few years later, it was framed and hung in their bedroom.

As far as the story goes, Miffy goes to the gallery and is confronted by art that seems to always reflect her being. Facing an existential crisis, she rebels and refuses to be a cute bunny.

Oh, I think that is another story.

In fact, the book ends with Miffy wanting to be an artist and declaring that “I think art galleries are fun”.

Given that Dick Bruna first published the story in 1997 it does make me wonder whether it was all an elaborating stroke of marketing genius from the Dutch museums. Apparently the book is quite hard to get now. It goes in and out of print – perhaps reflecting the current challenges facing art museums.

Or maybe that, too, is reading too much into it.

Iggy Peck, Architect is a charming rhyming story of a young fellow who loves to build buildings from whatever he has nearby – nappies, chalk, peaches, apples, pancakes, coconut pie – the list goes on. Until, that is, he meets his Grade Two teacher, Miss Lila Greer. She’s been scarred from an early childhood experience involving a skyscraper a lift and a French circus troupe.

The rhyming couplets that carry the story have a lovely rhythm and Beaty’s book has captured the imagination of both children enough to have clocked up many reads – quite a few repeat reads in the one night too! The illustrations by Roberts are great and the constructions built by Iggy Peck are splendid, and like the best illustrated books there are a few little hidden touches for young eyes to find.

I picked this book up at the SFMOMA bookshop on a visit to San Francisco but it is available quite widely including on Amazon.

Any book that excites children to consider architecture and building that doesn’t default to Bob the Builder is a welcome addition to the library!

I might be mad but I’ve decided to give yet another blog a go. This time I’m going to try talking about some of the books I’ve been reading to my children.

As a family we’ve read some great books but increasingly I’ve become frustrated by the lack of decent fiction to read as the children grow up. I’m not naive enough to think that ‘it used to be better in the old days’ – but do think that as book publishing has become cheaper, the market has become saturated and it is more difficult to separate the wheat from the chaff.

I’d like to think the the Web has made it easier to find the good stuff – as it has for so many other forms of media – but there’s something tactile and essential about flicking through a children’s book in a bookshop that isn’t yet replicated on the Web.

In fact, I’d expect that children’s books are undergoing an evolutionary leap as the iPad, the Kindle and other tablet devices take over. Children’s books will become ‘interactive’ by default – not just the experiments of a few like Penguin NZ.

It’ll be a while before I start writing about those though.

For now, I’m going through the shelves here at home and picking out a few favourites.

I hope you enjoy the selections.

(Oh, and the title image comes from the spines of some of my Ruth Manning-Sanders collections of fairy tales from the 1970s. I used to love the fairy tales from around the globe that they contained but on re-reading them to my own children I’ve been struck by how dated some of them feel.)